This is another one of those essays that just grew and grew as I wrote. Turns out I had a lot to say about anxiety and a childhood that seemed buried in the very distant past. As before, this post ends halfway through and I’ll be back next week with Part II!

“Round and around and around and around we go.” ~Rihanna

Sometimes I think we’re too quick to pathologize our emotions. For instance, therapy culture tells us that our emotions or lack thereof reflect our attachment styles (anxious or avoidant, in my case) and that we can achieve secure attachment by healing our inner child. But it strikes me that many times, our emotions are a natural response to our environment. I remember a therapist once recommending that I go on anti-depressants. I looked at him and said, “But I’m depressed because the situation I’m in is depressing. Why would I want medication to make me feel okay about this situation?”1

Since then, I’ve learned a great deal about various ways we can make ourselves feel better about the situations we find ourselves in. After all, the only element we can really control in any given situation is ourselves. If we know we’re about to embark on a period of hardship, we can (at least to some extent) make choices that will help us navigate the situation in a relatively positive way. Why make it more difficult than it needs to be? Why navigate it in a state of misery when we can choose to engage with it more . . . positively?

And indeed, age has taught me much about interacting with the world more positively and not indulging the emotional state that has dogged me my entire life: anxiety. To some extent, my relationship to anxiety is a natural one. I have lived under many conditions that would provoke anxiety in anyone – and Covid showed me that I can endure quite a bit more than the average person without falling into a pit of anxiety.

But there are many times when my anxiety is not necessarily a rational response to my circumstances. Anxiety, by nature, is preoccupied with the past and the future. Neither may be particularly relevant to the present, yet my mind will find itself burrowing away through some wormhole to revisit one or the other. So where did this tendency come from? Looking back, I can see that the seeds were sown in childhood. My odd childhood (it’s especially odd given how far I strayed from the path you might expect of someone with such a childhood) provided me with an innate tendency to view the world in a way that has proven both a reward and a cross to bear.

So, here’s a story about my life growing up in a, shall we say, cult-adjacent religious group. As far as would-be cults go, it was not a terrible one – to my knowledge, there were no instances of rampant sexual abuse (e.g. Children of God), obvious exploitation (e.g. “prosperity doctrine”), or other egregious examples of boundary crossing. There was, however, a near total preoccupation with the past and future coupled with a corresponding negation of individuality that lent itself to chronic self-doubt. How I saw the world and interacted with it was shaped by an uncertainty of self that I believe was planted by the belief system in which I was raised.

Were I pressed to describe my attitude towards faith, religion, or spirituality today, I’d say I’m simply disinterested. I’ve made peace with the things I missed out on as a child due to my parents’ religious beliefs. In fact, I respect the people I grew up with in church. I see them as a sincere, well-meaning, devout people who were part of a belief system that had some positive elements. Nonetheless, there was far too much space for negative elements that cause harm. Overall, I think I have earned my opinions on Christianity and religious belief in general as they came at quite a personal cost.2

It is challenging to talk about my upbringing in terms recognizable to a mainstream culture of Christianity because the people in this particular version of Christianity consciously reject nearly all of those terms. I was raised in a heavily independent strand of what is commonly referred to as the Plymouth Brethren. This is not what we called ourselves but as an adult, I have learned that it is how we are known to others. Our strand originated in Northern Ireland and Scotland. My father’s ancestors fled the Highland Clearances in Scotland and settled across the pond in a very similar region that remains to this day heavily populated by those of Scottish origin; his grandmother was a native Gaelic speaker. I imagine this peculiar sect appealed to some element of his dour cultural DNA. Both of my parents were converts.

There are different levels, if you will, of Plymouth Brethren-style “gatherings.” There are the Open Brethren, which we called the Bible chapels. The Open Brethren are . . . open; they accept Christians from other denominations to their Sunday worship. My strand was more conservative because we did not. In fact, we accepted no one into our services unless they had a “letter of commendation” from the elders at their “assembly,” as we called our churches. In this sense, you might call us Closed Brethren.3 There is a version that is even more conservative called the Exclusive Brethren and it is a group from this strand, the Taylorites, who are known in Australia for being a full-blown cult. Yes, compounds and all.4

It is thus fair to call my upbringing “cult adjacent” in nature. Here are some characteristics of our sect (it turns out there are rather a lot):

We went to “meeting,” not church. We were an “assembly” or a gathering; the church is a body of people.

The buildings we met in were plain and free of any imagery/iconography. The only elements permitted were large painted texts of Bible verses.

We didn’t believe in the use of musical instruments. Instead, we sang hymns a cappella. Only one particular hymnbook of theologically sound hymns was allowed. Every assembly has an informal hymn leader who starts the hymn in question, ideally in the right key, for everyone else to join in.

Women wore head coverings at assembly gatherings, whether within the church building or not. I preferred a wool beret or a mantilla as both could be shoved into a purse when adults weren’t looking.

Women were silent at all times in assembly gatherings.

Women were not allowed to cut their hair, wear makeup, fashion elaborate hairstyles, have pierced ears, wear red shoes or pants, or otherwise focus on their appearance in an attention-seeking way. Men could not wear a wedding ring. We were a modest people.

The only acceptable translation of the Bible was the King James.5

As strongly counter-cultural separatists (from 99.9% of Christianity and 100% of mainstream culture), we did not believe in owning televisions or radios.6

We did not believe in political participation of any kind. This meant we did not vote. We probably wouldn’t have paid our taxes were it not for Caesar.7

Women did not work or pursue an education.8

Sunday morning services were 90 minutes of prayer and singing. Sunday school was 45 minutes of class. Sunday afternoons were 60 minutes of Bible study. Sunday evening gospel meetings were 60 minutes of preaching. Tuesdays were for prayer meetings, Wednesdays for youth group, and Thursdays for Bible study again.

Summers were for tent revival-style meetings, in which we would spend anywhere from two to 12 weeks attending nightly gospel meetings in a large tent in a conspicuous location (e.g. right next to a highway or a theme park).

Saturdays were for street preaching.

Holidays were for Bible conferences.

We practiced shunning.

We seemed hyper fixated on dispensationalism. I’ve yet to encounter any other Christian denomination that even seems aware of it.

Perhaps the most obvious distinction between my evangelical fundamentalist sect and those more public is the fact that we had no laity or clergy, no affiliation with any denomination, and no desire for a sectarian identity. There were only independently run assemblies counselled by “elders” informally appointed by their peers, “the Brethren”. This made each assembly heavily localized and it is difficult to speak in broad strokes about their practices. I knew some children in other assemblies who weren’t allowed to participate in organized sports, for instance, whereas we all did. Some girls skied in “snow skirts”; no matter what my parents tried to force on me, I refused to ever ski in a snow skirt.

But on the whole, all assemblies had the characteristics listed above. I am one of eight children, six of whom were born in a ten-year span. I am the second oldest and compared to my five feral brothers, I was the one marked by our religious faith.9 I was the one who looked visibly different from everyone else, from my long skirts to my uncut hair to my lack of makeup or anything particularly fashionable. We could try to hide our ignorance of popular culture, but I couldn’t hide the fact that I looked different from all the other girls at my elementary school – even the recent immigrants who could barely speak English fit in better, visually at least, than I did.

I call us “culty” by virtue of the monopoly of our time. The degree of control that the group exercised over over one’s life varied on a parental basis. My parents are exceptionally skilled at compartmentalization, which meant we generally followed the rules to avoid conflicts but we all knew we’d break them eventually. My father, in particular, was a true believer – but not a full hook-line-and-sinker church type (I think he really just liked the literary, intellectual bent of this sect).10 Amongst us children, we generally tried to forget we were part of the group altogether. It was difficult. There was a great deal of Bible reading and a great many rules to follow.

One (arguable) upside of the group I grew up in is they did not much care about anything that happened in the world. This spared me the culture wars and politicization of Christianity that occurs in the United States, for which I am deeply grateful. My assembly did not even take a clear stance on abortion (to my recollection, as this was not a high-profile issue in the slightest, I believe such decisions were deemed between a woman and God because no one should be so arrogant as to claim they know when God infuses the body with a soul).

Another upside was that the intensity of their focus on worshipping the right way distracted them from overinvolvement in one’s personal life, bedroom, and so on. There were certainly homophobic and deeply misogynistic ideas floating about, but an assembly full of septuagenarians seemed blissfully unaware of the potential sex lives of the young amongst them. Any “purity culture”-type instruction generally came from books purchased at Christian bookstores, not the mouths of the elders.

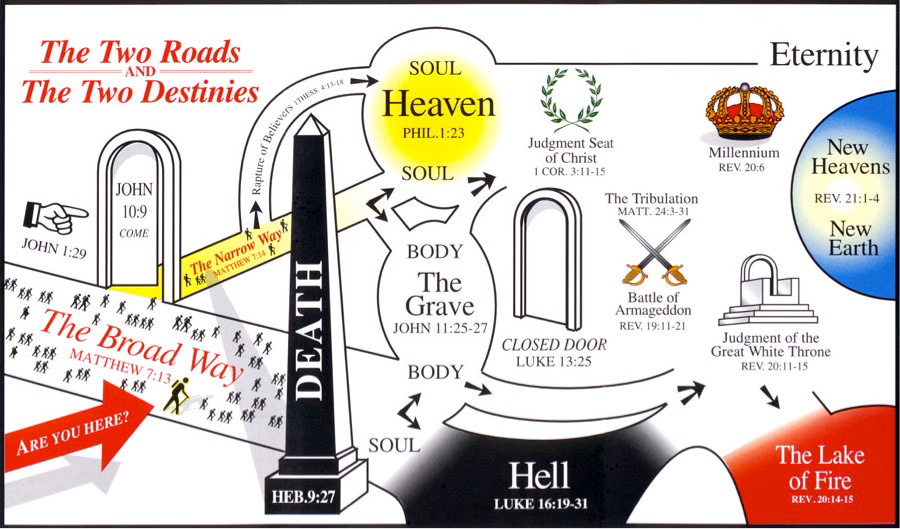

But this was a two-edged sword as the focus on worship, and this chart in particular, featured prominently in my childhood. I remember being terrified of hell for as long as I have any memories at all.

It was all very confusing but Hell yawned ahead, clearly ready to swallow you up just when you least expected it. Even a side trip could get you sent straight to the Lake of Fire, which seemed like Hell but worse. Even the Narrow Way couldn’t secure you a get-out-of-Hell-free pass! The best way to go was obviously the Rapture, which meant you wouldn’t die at all. And so I spent my childhood equally terrified that the Rapture had occurred and I had been left behind.

I’ve heard the ethos of my upbringing is very similar to that of Mennonites, who were not so different from us. We were certainly joined in a grim outlook on the present: none of it matters. This life is hardship and pain. We endure the present for the sake of our lives after death, which is when all that perseverance will be made worthwhile. Everything around us is “for the fire” (God’s destruction of Earth with fire sometime after the Battle of Armageddon, I think), so there’s no point in trying to preserve any of it. The only thing that really matters is whether you’re on the Broad or Narrow Way.

This rather distressing outlook on the present was grounded in both the future and the past. The future was where we would reap our rewards. These rewards would be doled out on the basis of our past – that moment in time when we acknowledged Jesus Christ as our Saviour and were delivered from eternal damnation. For this reason, I believe I was “saved” upwards of 100 times before the age of seven. Given the stakes, one really wanted to make sure one got it right. Naturally, this is a recipe for deep anxiety.

Another way that Christianity, and probably any faith with a domineering higher power of sorts, hollows out your sense of self is by imparting the message that you can’t trust yourself. Your instincts are human and human nature is evil, which means you’re evil. Even if you’re saved, you’re evil by virtue of your humanity.

So, my sect told us:

don’t follow your heart. God said, “Take up your cross and follow me.”

don’t be true to yourself. God said, “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny himself.”

don’t believe in yourself. God said, “Believe in me.”

don’t trust your own truth. God said, “I am the truth.”

don’t base decisions on what makes you happy. God said, “What will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his own soul?”

In short, don’t listen to your evil human intuition. Don’t pursue YOUR hopes and dreams. Don’t explore YOUR sense of self, your interests, your own notions of justice and happiness. Instead, subjugate your evil flesh. Serve God, or die.

Mentally, I left my faith around the same time I left home for university. I lived in a Christian sorority that imposed their version of Christianity on us and while I still accepted the broad tenets of the faith, I knew I was over the extreme subjugation of my (evil, human) flesh. After I got married, I dabbled again in Christianity by attending a megachurch in Southern California. I think I wondered if I pursued an entirely different version of Christianity – the polar opposite, one might say – than I’d grown up with, maybe I’d uncover something new. Instead, it all proved far less literary, less interesting, and less . . . authentic than what I’d already been exposed to.

By my late 20s, I was done with Christianity for good. I had spent a solid fifteen years memorizing the King James Bible at length. I had sacrificed my childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood to my faith. I had lived in fear of the Lake of Fire for long enough. Never again would I waste time thinking about the Rapture or the Millennium. I didn’t care if the four horsemen appeared on the horizon to harvest my soul and my soul alone; I was done with it all. Even if it eventually proved true, I was willing to take my chances with the judgment in front of the Great White Throne. Better that than damnation to a wasted life on Earth.

I think exploration of the roots of anxiety or any other chronic mental state can help us better understand how our emotions were once rational responses to our environment and experiences. A belief system that positions you in a bleak present stuck somewhere between an existential turning point in the past and a potentially torturous future sets you up to struggle to live in the here and now. It teaches you to not trust anything that feels too good, too pleasurable, too hedonistic. Life’s joys should be rejected in favour of strict spiritual discipline. Above all, never ever fit in with the masses. You are set apart, holy and sanctified (but also sinful and evil), not meant for this world.

Given that, how could my worldview be marked by anything but anxiety? With every major life decision, I found myself wracked with uncertainty. I completed two years of pre-med at university before realizing that I had no stomach for blood; I’d chosen medicine simply because it was ethical. Medicine helped others. Unlike business or economics, it wasn’t concerned exclusively with The Things of This World. (My real interest was actually International Relations, but I had no idea what this was and given that it involved government, it didn’t seem particularly ethical. And who would base their decisions on their own actual interests over inculcated ethics?).

My uncertainty weakened my commitment and I felt myself floundering as I searched for a direction, any direction. What did I want? Truth be told, I had no idea. I hadn’t really expected to outlive the Rapture. I was preoccupied with death because it had always seemed so easy to die. In fact, the most likely outcome I had to look forward to was probably some form of interminable pain. But actually living – pursuing a good life BEFORE death? This hadn’t been the subject of much conversation in my first two decades of life. What on earth did one do when one had more choices than just the kind that determined the fate of one’s soul?

I’m not naturally depressive. Some people are – clinically so – and I do not claim to have any insight into where their emotions originate.

Truth be told, I am not much impressed by believers of any sort who are quick to share loud opinions but make few sacrifices (in terms of appearance, lifestyle, and behaviour) for their faith.

Here we are on Wikipedia. This is us, although the write-up is not entirely accurate as we were decidedly not Open Brethren.

Oddly enough, some Taylorite practices seem more permissive than ours ever were.

I was weaned on the King James. While my high school classmates found the task of reading Shakespeare bewildering, I found it a breeze. After all, he was of the same era as King James.

We didn’t mind computers because those were a tool. My brothers and I had fairly unfettered access to a computer that we eventually cajoled our parents into allowing us to combine with a VCR. By our mid-teens, we were watching at least some movies. We were also VERY early adopters of the internet. The septuagenarian elders of my church were unbothered by this computer stuff. Little did they know it would go on to let FAR more Satan into our lives than television or radio ever would or could.

Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s and render unto God that which is God’s.

I knew, from a young age, that this is what would sever my ties to the church. We were raised to leave home immediately at age 18 (preferably earlier) and to attend university so we would “stop being wet behind the ears and get a real job,” according to my father.

I’ve always had an affinity for Sikhism as one of the few religions that forces men to wear the faith. It seems most religions are predictably focused on controlling the appearance of women. All fundamentalist evangelical Christian sects certainly are.

Both of my parents liked the black-and-white nature of the rules of this belief system. It turned out they needed the rules to behave. Once the rules were gone, neither was interested in behaving on any level.

Indeed. Our society is engulfed in advertising that convinces us we will be better off with this product or this pair of pants. Some of the new products can be very useful. We need to practice “delayed gratification” in order to become free from debt and stop comparing ourselves to our neighbor.

I would be interested to see pics of you and your family dressed properly for your religious group, if it’s not to uncomfortable

Hi Liya, I read this with great interest because my dad grew up in an Apostolic faith that had many similarities to what you described. I wrote a little bit about it in an article called Belonging and Identity. I grew up in a farming community with hundreds of cousins around us, but my family didn't join that church (I visited a few times when I was young, and later in life for funerals or other special events), so I didn't feel a sense of belonging. I'm grateful that I didn't grow up in a legalistic setting like this. My faith has been something very real to me, and it's still very central to my life. But it's a relationship with Christ, not the trappings of a religion, that has been so transformative to me. Just wanted to say I can understand how these early experiences/teaching would have impacted you. Sometimes my cousins leave the stricter faith of their parents and listening to them talk about discovering the wonder and beauty of God's grace and love has always been a joy to me. When all they knew was legalism and the threat of condemnation, it's no wonder they felt like rebelling. I personally do believe the Bible is living and active and my beliefs have formed as I have studied His word. But the Savior who changed my life and gave me hope calls me Friend (John 15) and His banner over me is love. I don't have to perform to earn His love. I simply need to accept the free gift of His grace. I'm not seeking to convince you of anything, just sharing how my own beliefs came to be a joyful part of my inner life and a huge source of strength and joy. Very happy to read your work today. Thanks for sharing your background and how this has impacted you.